|

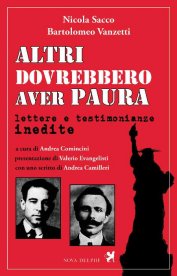

Altri dovrebbero aver paura è una preziosa raccolta di lettere e testimonianze di Nicola Sacco e Bartolomeo Vanzetti mai apparsi in Italia o all’estero. A differenza di quanto pubblicato precedentemente queste missive aiutano a sviluppare una riflessione puntuale sul sentire dei due protagonisti riguardo alla situazione politica nell’America di quegli anni. A tale documentazione si aggiungono le loro riflessioni su alcuni argomenti specifici: i giudizi sul movimento proletario internazionale, il ruolo della Chiesa nel mondo e la battaglia contro il pregiudizio religioso, le riflessioni sul fascismo in Italia e quelle riguardanti l’oppressione cui erano sottoposti il movimento anarchico e il comunismo. Un libro imprescindibile, quindi, per chiunque voglia conoscere attraverso documenti inediti l’esperienza e il coraggio dei due emigrati italiani condannati e uccisi il 23 agosto del 1927.

Completano il volume testi di Valerio Evangelisti, Andrea Camilleri, Andrea Comincini.

Andrea Comincini (1976), dopo essersi laureato in Filosofia, ha conseguito un Dottorato di ricerca presso lo University College Dublin. Giornalista pubblicista, scrittore e ricercatore indipendente, ha pubblicato un’edizione critica della Persuasione e la Rettorica di Carlo Michelstaedter e una monografia sullo stesso autore. Le sue ricerche hanno come oggetto l’evoluzione del pensiero materialista nella filosofia e nella storia.

Il testo di Andrea Camilleri è la riproposizione dell'intervento pubblicato sul

New York Times il 23 agosto 2007, che riportiamo anche in calce.

Il testo, ritradotto dall'inglese all'italiano, è stato pubblicato il 24 agosto 2007 su

La Repubblica e

La Stampa.

Cliccare sui link alle testate o consultare la

Rassegna Stampa per leggere gli articoli.

Italy’s American Baggage

The century we left behind us just seven years ago was brilliantly described by the British historian Eric Hobsbawm as “the short century.” But perhaps a more exact definition would be “the compressed century,” for never has a period of 100 years seen so many world wars, so many scientific and technological advances, so many revolutions, so many epoch-making events piled almost one on top of the other. Indeed, the past century seems rather like a suitcase too small to hold everything that happened: it’s too crammed with used clothing, some of which hinders us from closing it and putting it away in the attic once and for all.

One such hindrance is the case of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. In the previous century millions of men and women died in wars, epidemics, genocides and persecutions, and unfortunately their memory is all too much in danger of vanishing. Yet the deaths of Sacco and Vanzetti in the electric chair 80 years ago today, as much as those of John and Robert Kennedy by assassins’ bullets, are destined to remain in our minds. Perhaps this is because, as with the Kennedy brothers, we still have difficulty accepting the reasons, or lack thereof, for their deaths. And in Italy, where meaningless (or all too meaningful) killing has long been part of the political landscape, this uneasiness is keenly felt.

In the case of Sacco and Vanzetti, it seemed immediately clear to many in Europe and the United States that their arrest in 1920 — initially for possession of weapons and subversive pamphlets, then on a charge of double murder committed during a robbery in Massachusetts — the three trials that followed, and their subsequent death sentences were intended to make an example of them. And this regardless of the utter lack of evidence against them and in spite of defense testimony by a participant in the robbery who said he’d never seen the two Italians.

The perception was that Sacco, a shoemaker, and Vanzetti, a fishmonger, were the victims of a wave of repression sweeping Woodrow Wilson’s America. In Italy, committees and organizations condemning the sentence sprouted up as soon as it was announced. By the time the sentence was carried out in 1927, Fascism had been in power in Italy for nearly five years and was brutally consolidating its dictatorship, persecuting and imprisoning anyone hostile to the regime — including anarchists, naturally. And yet when Sacco and Vanzetti were executed, the biggest Italian daily, Milan’s Corriere della Sera, did not hesitate to give the story a six-column headline. Standing out glaringly among the subheads was the assertion: “They were innocent.”

There is probably not a single Italian newspaper that has not devoted an article to the case every Aug. 23 from 1945 to the present. In 1977, much prominence was given to the news that Michael Dukakis, then the governor of Massachusetts, officially recognized the miscarriage of justice and rehabilitated the memory of Sacco and Vanzetti.

In Italy, their story became the subject of a drama that enjoyed great success on the stage before it was made, in 1971, into an excellent film by Giuliano Montaldo, with splendid performances and a soundtrack by Ennio Morricone that included songs by Joan Baez. (Woody Guthrie’s 1960 album, “Ballads of Sacco and Vanzetti”, also enjoyed wide distribution in Italy.) And in 2005, the Italian state TV network RAI produced a long program on the two executed Italians. (Oddly enough, for some reason the network has never shown “The Sacco-Vanzetti Story,” a 1960 made-for-television movie directed by Sidney Lumet, even though it acquired the rights long ago.)

And now an Italian Internet site has an active discussion of the two anarchists’ case. One of the many contributors writes: “Those poor guys were only guilty of fighting racism and xenophobia.” Another: “What has changed? The death penalty still exists in America, even for those who are sometimes innocent, and racism and xenophobia are on the rise ...” And a third: “It is impossible to compare that period with this one. Nowadays the courts make mistakes, serious ones, but mistakes nevertheless, whereas back then outright murder was committed, for purely political ends. And even if racism is still alive and well in the United States, great progress has been made.” Finally, a conclusion: “That was a nasty affair in a difficult time.”

A nasty affair indeed, if Italians, generally indulgent toward the land that has welcomed so many of its destitute emigrants, are still dwelling on it after all these years. Apparently the debate is still ongoing. A sign, perhaps, that the wound has not yet healed. And that we still can’t close the suitcase, no matter how hard we try.

Andrea Camilleri

|